John Munro

John Montgomery Munro was the first child of Alexander and Janet Munro. He was born on September 12th, 1891 in the old Pederson house on the family farm at Crystal Springs, Bainbridge Island, Washington. As the first of ten children, much was expected of John. He knew the value of hard work and education, and he had an ingrained sense of integrity. He was also ambidextrous and could write in perfect cursive with either hand.

When John was a child Native Americans spent the summers camped on the beaches of Bainbridge Island, often digging clams to sell in Seattle. One day John and his brother Duncan heard a rhythmic noise in the woods near their east property line. When they explored, they found native people carving a log into a canoe right where the tree had fallen. The boys watched the canoe take shape, inside and out, before it was moved to the beach. They both remembered and marveled at this throughout their lives.

It’s unknown what level of education John completed. Many of his brothers and sisters graduated from the eighth grade on Bainbridge Island and then attended High School in Seattle. Perhaps this was the case for John. We do know that after he finished school he apprenticed to an architect in Seattle and lived with his employer’s family. We have one photograph of him at a draftsman’s table in the architect’s office.

John became very ill while working in Seattle and returned home to Bainbridge. He was nineteen or twenty at the time. For many years there was a sharp disagreement in the family about John’s illness. Some adamantly believed that he had the Spanish Flu. Others believed that he had Tuberculosis which, in that place and time, carried a heavy stigma. At the height of his illness he lived in a tent on the south side of the house. His mother cared for him, feeding him raw eggs for their high nutrition and easy digestibility. She also kept a large kettle of boiling water on the cook stove by the back door and every dish or item that came back from the tent was immediately placed In boiling water to sterilized it. It’s easy to imagine her fear. How could she save her first born child and at the same time keep the remaining nine healthy. Her youngest, James, was an infant or toddler.

John survived his illness, but he never again thrived. Many times he would regain his strength and stamina and begin to live a fuller life, but any virus or illness would seriously debilitate him and recovery was always painfully slow. Although he worked various jobs around Bainbridge Island and at the Naval Ship Yard, his health never allowed him to build a career. His most memorable job was as the first school bus driver on Bainbridge Island. According to Picture Bainbridge, A Pictorial History of Bainbridge Island he “operated the island’s first school bus to transport Crystal Springs kids to Winslow High School for the princely sum of $7 per day. His contract required him to ‘furnish suitable conveyance equipped with comfortable seats and . . . top and side curtains which shall be used during stormy and inclement weather’.” The suitable conveyance was John’s Ford Model T truck. At times, three or four of the children on his route were his younger brothers or sisters.

John also farmed the family place, raising produce, keeping bees and milking a cow or two. Before there was a road to Westwood (north of the family place) there was just a trail that led from house to house all the way to the end. Most of these were summer homes for people who lived in Seattle and elsewhere. John delivered milk, eggs, bread, firewood, etc. along the trail during the summer months, and kept their old homes warm in the winter. He also had a delivery route for the Seattle Post Intelligencer, made soap for the family and kept all the neighborhood boats running. Ralph remembers being stung by perhaps twenty honey bees when he was about eight years old. Uncle John calmly sat with him and removed the stingers, scraping each with his pocket knife.

As his mother aged, John became her caregiver and the caretaker of the home and farm. By this time his brother James was an attorney with a practice in Bremerton who made sure the bills were paid and there was always food on the table.

After their mother’s death in 1952, John and James continued to share the family home. John was always a quiet, independent presence. He loved his extended family in an undemonstrative way. When James and his wife, Carolyn, began their family in the late 1950’s John would switch between the quiet presence in the background and the helping hand. On more than one occasion he took his turn walking with a colicky baby. Although by the fourth baby he was spending more and more time in his room or next door at his sister Mary’s house.

Growing up in the house with Uncle John, I knew very little about him. I knew that he loved his Reader’s Digest and that he often mixed together all the food on his plate and then added ketchup. I learned with time that he had a profound intelligence that he rarely shared with others. His focus was always keeping things simple, living his daily life by the old ways, and preserving the family place and the memories that were attached to it. John passed away on August 16th, 1986.

Elizabeth Munro Berry

A Couple Stories from Ralph:

When I was about six, John’s bees swarmed. They flew right over the top of the hill and down to our yard. They hung in a big swarm in our tree for about two hours. Then they swarmed again and flew down over the beach and right across the bay.

John came down the hill and asked me where they went. I pointed to where they had flown to across the bay. He said, ‘Oh that might be the Rue’s place. The Rue’s were old friends. He found a box and rowed across the bay in the big skiff. About two hours later he rowed back with his bees in the box on the back seat of the boat.

Another time ………… Mom and I were driving home from school. It was a windy, rainy day. Mom saw Uncle John’s cow grazing beside the road right at Point White [better known as Truman’s corner], and it was dragging a broken rope. We parked the car and walked the cow with the broken rope all the way home. I was small and it was a long walk. When we reached the house, Mom tied the cow to the mailbox that’s still there. Then she went to get Uncle John. He came down the hill and looked at the cow and said,,,,,,,,,, ‘that’s not my cow!’ His cow was up behind the barn. He walked away and left my mother to take the cow back to where we found it. Rather embarrassing.

Ralph

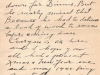

John’s letters to his brother Bill are a precious glimpse into his life and personality. We’re very fortunate to have these letters which were saved by Bill’s daughter, Cecelia, and shared with us by Cecelia’s daughter, Patty Wiegert. You can view them below.